The Agency Problem

Why use-case for AI Agents has so far been underwhelming

The Agency Problem

Why the use-case for AI agents has so far been underwhelming

The excitement around AI agents feels off to me. A friend recently showed me how he’s using OpenClaw (formerly Clawdbot / Moltbot) to automate parts of his life: paying bills, managing routine tasks, buying vitamins.

While cool in demo form, it made me ask: why are we celebrating automation of friction that shouldn’t exist in the first place?

I’ve set up direct debits for all my recurring payments. It took a few minutes and I check in only every six months or so. The tasks my friend spends hours manually juggling are activities that could arguably be eliminated, not automated.

This distinction feels crucial. Many proponents are excited because agents delegate existing tasks more effectively — but that’s a shallow measure of progress. It’s like cheering a robot for polishing rusty iron when you could redesign the machine to never produce rust in the first place.

The Nice Email Fallacy

A clarifying moment for me came from a recent piece on adversarial reasoning in AI

The idea that current models are optimized to produce reasonable text rather than strategically effective outcomes.

Here’s the classic example: you’ve just joined a new job and need a senior designer to review your work. You ask an LLM to draft a Slack message. It produces something polite, deferential, and “just right” in isolation.

But politeness isn’t the real objective — urgency, clarity, and leverage are. A human who’s been in that organisation longer knows how the recipient actually reads messages: what gets prioritised, how ambiguity gets deprioritised, and what signals lead to action. The message that “sounded good” to your LLM or finance-savvy friend ends up buried in triage.

This is not a bug — it’s a fundamental limitation of how these models are trained: they reproduce what looks reasonable to humans, not what survives contact with a self-interested, adaptive environment.

In organisational life, people don’t respond to static artifacts — they respond to incentives, hidden states, priorities, and power dynamics. Agents that don’t model that context are, at best, generating polite text and, at worst, blinding you to the real dynamics underneath.

Automating Workflows vs Redesigning Them

This leads to what I think is the real disconnect:

People aren’t craving delegation. They’re craving a reduction in unnecessary work.

Right now, almost all the agent hype frames the narrative as:

“AI will free you from menial tasks”

“AI will be your digital assistant”

“AI will take over repetitive work”

But much of what we call “repetitive work” is a symptom of outdated organisational design — not a permanent fixture of knowledge work.

Organisations grew big because they needed bodies to complete tasks and guardrails to contain risk. Complex reporting lines, SLA targets, coordination overhead, approval chains — all exist not because they’re valuable in themselves, but because of risk aversion and legacy process.

Take customer support: if you commit to answering calls within two minutes for a million customers, you must staff for those peaks. That’s not a technology limitation — that’s a contractual commitment infused with risk calculation. Pull one lever (AI automating responses) and the SLA still exists — the human time cost just becomes hidden or shifted, not eliminated.

The real winners in the coming shift won’t be companies that automate existing work. They’ll be the ones that automate the need for that work in the first place.

What Scales vs What Doesn’t

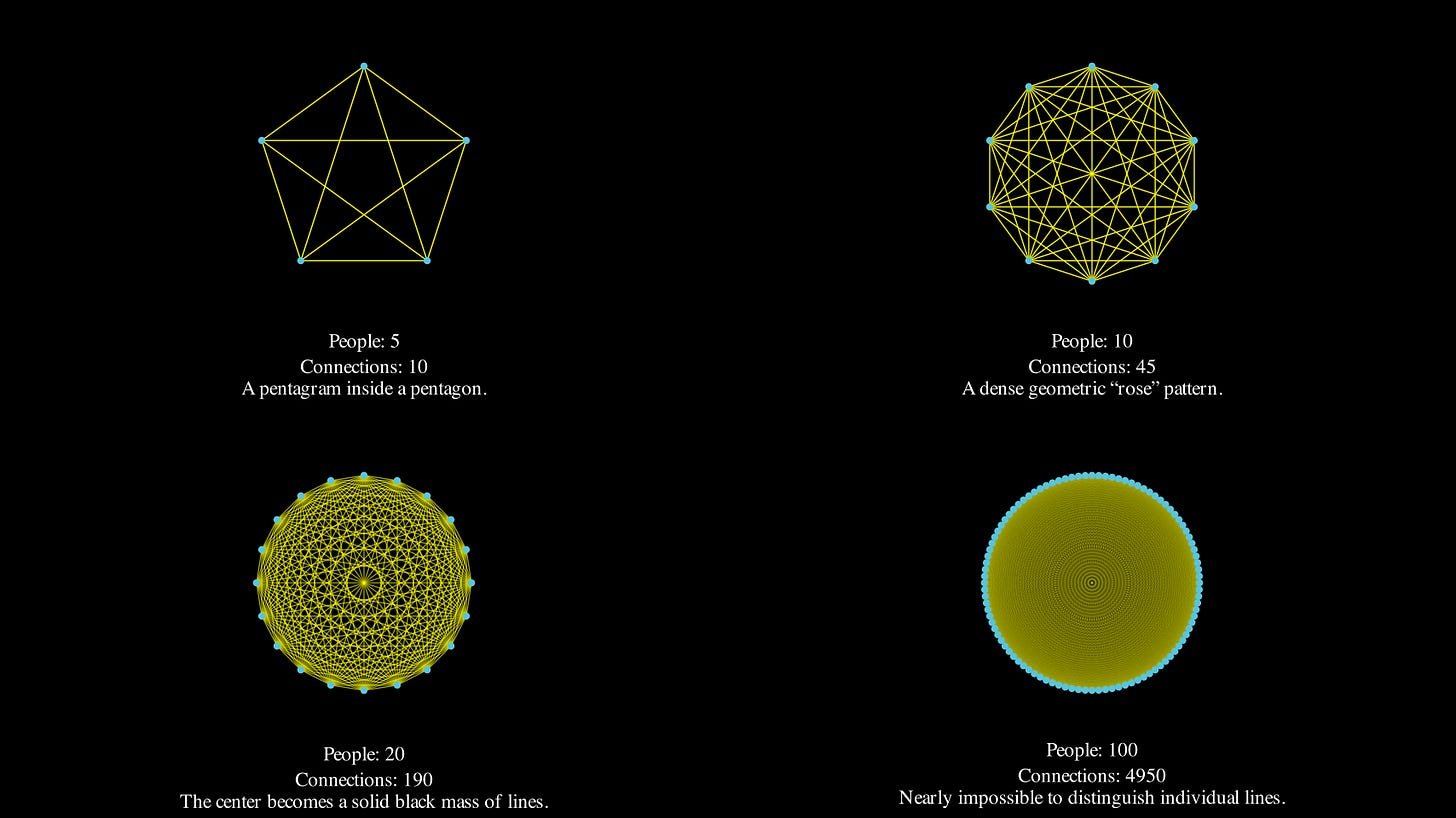

Metcalfe’s Law reminds us that the number of interconnections grows quadratically with the number of participants. In human systems, that means coordination overhead becomes the dominant cost as organisations grow. Communication, approval chains, shared context, alignment: these are the expenses that don’t scale with automation; they scale with relationships. Agents don’t collapse this combinatorial growth, they merely participate in it.

Good agents automate tasks like scheduling, data retrieval, routine reminders — but they don’t eliminate the coordination problems embedded in organisational structures.

A Smaller Loop: Thought → Build → Artifact

What feels genuinely transformative about AI isn’t delegation — it’s the shrinking of the loop between:

Thought → Build → Artifact

The promise of AI isn’t that it executes our to-dos; it’s that it compresses the cycle of creation. It lets individuals — not just institutions — convert ideas into real outcomes rapidly and without massive bureaucracy.

This is why open weight models and local autonomy matter: they give individuals agency over knowledge work, not just incremental efficiency in legacy task lists. Agents should magnify our abilities, not negotiate broken systems for us.

Addendum: Risk and Organisational Scale

[These are early thoughts on what may turn into a longer article]

One reason legacy organisations persist is risk aversion — especially reputational risk. Large companies dilute individual responsibility to insulate against mistakes. But that same protection breeds inertia: the organisation’s primary goal becomes avoid failing visibly, not operate effectively.

Smaller organisations — and individuals — often tolerate higher risk because they carry both upside and downside directly. That tolerance can be a competitive advantage: nimble decisions, rapid iteration, fewer layers of approval. The question isn’t just can agents do tasks, it’s can smaller entities leverage them to out-compete monoliths that are risk-averse by design?

There’s risk inside and outside organisations. Many people are not comfortable taking on more responsibility or the consequences that come with it. But agency isn’t merely about delegation; it’s about ownership of outcomes.

Closing Thought

We’re early in the agent era. The demos are flashy. The headlines are hyperbolic. Yet beneath those stories lies a deeper lesson:

AI agents will be truly valuable not when they mimic what we already do, but when they help us rethink why we do it.